Sally makes landfall, continues to drench Coast

Published 5:24 am Wednesday, September 16, 2020

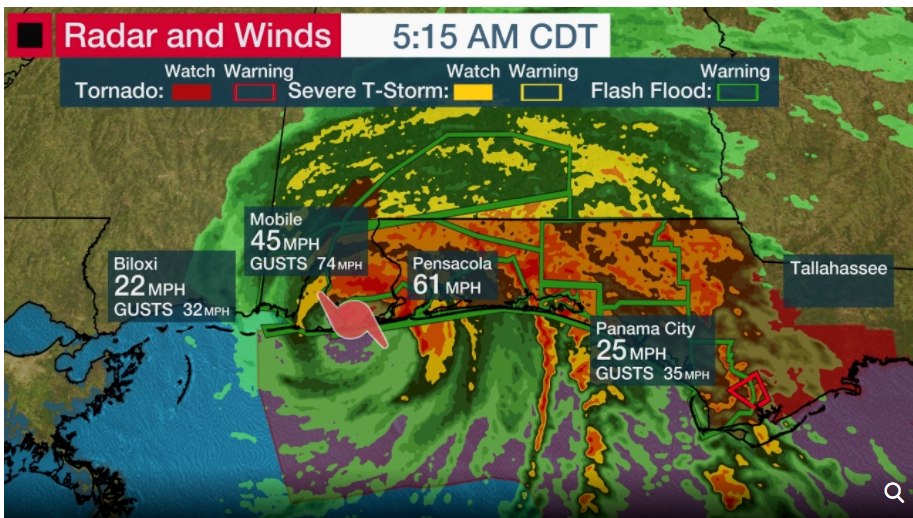

- Image courtesy The Weather Channel

PENSACOLA, Fla. (AP) — A newly strengthened Hurricane Sally made landfall near Gulf Shores about 5 a.m. Wednesday as a Category 2 storm.

Sally pummeled the Florida Panhandle and south Alabama with sideways rain, beach-covering storm surges, strong winds and power outages early Wednesday, moving toward shore at an agonizingly slow pace that promised a drawn out drenching and possible record floods.

Some 150,000 homes and businesses had lost electricity by early Wednesday, according to the poweroutage.us site. A curfew was called in the coastal Alabama city of Gulf Shores due to life-threatening conditions. In the Panhandle’s Escambia County, Chief Sheriff’s Deputy Chip Simmons vowed to keep deputies out with residents as long as physically possible. The county includes Pensacola, one of the largest cities on the Gulf Coast.

“The sheriff’s office will be there until we can no longer safely be out there, and then and only then will we pull our deputies in,” Simmons said at a storm briefing late Tuesday.

This for a storm that, during the weekend, appeared to be headed for New Orleans. “Obviously this shows what we’ve known for a long time with storms – they are unpredictable,” Pensacola Mayor Grover Robinson IV said.

Hurricane Sally’s northern eyewall was raking the Gulf Coast with hurricane-force winds and rain from Pensacola Beach, Florida westward to Dauphin Island, Alabama, the National Hurricane Center said.

Forecasters say landfall came about 5 a.m. Wednesday when the center of the very slow moving hurricane crossed land near Gulf Shores as a Category 2. Sally remains centered about 50 miles (75 kilometers) south-southeast of Mobile, Alabama and 40 miles (65 kilometers) southwest of Pensacola, Florida, with top winds of 105 mph (165 kmh), moving north-northeast at 3 mph (6 kmh).

Stacy Stewart, a senior specialist with the National Hurricane Center says the Category 2 hurricane could strengthen further before the entire eyewall moves inland.

The hurricane will bring “catastrophic and life threatening” rainfall over portions of the Gulf Coast, Florida panhandle and southeastern Alabama through Wednesday night, he said. Stewart said the hazards associated with the hurricane are going to continue after it makes landfall, with the storm producing heavy rainfall Wednesday night and Thursday over portions of central and southern Georgia.

Sally was a rare storm that could make history, said Ed Rappaport, deputy director of the National Hurricane Center.

“Sally has a characteristic that isn’t often seen and that’s a slow forward speed and that’s going to exacerbate the flooding,” Rappaport told The Associated Press.

He likened the storm’s slow progression to that of Hurricane Harvey, which swamped Houston in 2017. Up to 30 inches (76 centimeters) of rain could fall in some spots, and “that would be record-setting in some locations,” Rappaport said in an interview Tuesday night.

Although the hurricane had the Alabama and Florida coasts in its sights Wednesday, its effects were felt all along the northern Gulf Coast. Low lying properties in southeast Louisiana were swamped by the surge. Water covered Mississippi beaches and parts of the highway that runs parallel to them. Two large casino boats broke loose from a dock where they were undergoing construction work in Alabama.

In Orange Beach, Alabama, Chris Parks, a resident of Nashua, New Hampshire, spent the night monitoring the storm and taking care of his infant child as strong winds battered his family’s hotel room. The family was visiting the state before their return flight back to New Hampshire was canceled. Now, they are stuck in Alabama until Friday. “I’m just glad we are together,” Parks said. “The wind is crazy. You can hear solid heavy objects blowing through the air and hitting the building.”

Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves urged people in the southern part of his state to prepare for the potential for flash flooding.

As Sally’s outer bands reached the Gulf Coast, the manager of an alligator ranch in Moss Point, Mississippi, was hoping he wouldn’t have to live a repeat of what happened at the gator farm in 2005. That’s when about 250 alligators escaped their enclosures during Hurricane Katrina’s storm surge.

Gulf Coast Gator Ranch & Tours Manager Tim Parker says Sally has been a stressful storm because forecasters were predicting a storm surge of as much as 9 feet in the area. But he has felt some relief after seeing the surge predictions had gone down.

After dumping rain on the coast Wednesday, Sally was forecast to bring heavy downpours to parts of Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and the Carolinas later in the week.

Sally’s power was an irresistible draw for some in its path.

With heavy rains pelting Navarre Beach, Fla., and the wind-whipped surf pounding, a steady stream of people walked down the wooden boardwalk at a park for a look at the scene Tuesday afternoon.

Rebecca Studstill, who lives inland, was wary of staying too long, noting that police close bridges once the wind and water get too high. With Hurricane Sally expected to dump rain for days, the problem could be worse than normal, she said.

“Just hunkering down would probably be the best thing for folks out here,” she said.

Meanwhile, Tropical Storm Teddy has now become a hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 100 mph (160 kph) the National Hurricane Center said early Wednesday.

Teddy is located about 820 miles (1,335 km) east of the Lesser Antilles. Hurricane-force winds extend outward up to 25 miles (40 km) from the center and tropical-storm-force winds extend outward up to 175 miles (281 km).

Some strengthening is forecast during the next few days, and Teddy is likely to become a major hurricane later Wednesday and could reach Category 4 strength on Thursday.

___

Wang reported from Mobile, Alabama and Martin, from Marietta, Georgia. Associated Press reporters Russ Bynum in Savannah, Georgia; Sophia Tulp and Haleluya Hadero in Atlanta; Tamara Lush in St. Petersburg, Florida; Rebecca Santana in New Orleans; Emily Wagster Pettus in Jackson, Mississippi and Kim Chandler in Montgomery, Alabama, contributed to this report.